On Writing by Stephen King...

Get ready to sit down with the master of horr...

By Adonis Monahan1657

0

By sheer happenstance, I found myself agreeing to write a review of this book. Always an avid reader, especially of crime fiction, I had never ventured, somehow, into the realm of True Crime. But, my word was my word!

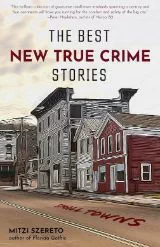

There are 15 short stories in this anthology, put together by Mitzi Szereto on small town crimes, and they hail from places as varied as Tasmania, Trinidad & Tobago, the Orkneys, Tuscany, Wales and Alabama. That appealed to me because I am a geographer at heart and have a yen for distant places. What I especially liked (being also a history buff) was the inclusion of crimes committed in previous eras, such as the 1884 tale of The Doctor, the Dentist and the Dairyman’s Daughter, set in Carmarthen, Wales; the 1935 case of a woman in Ontario, Canada who was found guilty of poisoning her husband (20 Cents Worth of Arsenic); and, the unsolved murder of a village girl in the Tuscan Hills in 1947 (La Bella Elvira). Each story in the anthology gives a flavor of the times, a sense of place, but also insights into the methods and processes of criminal investigation across these varied settings. A story from Ecuador (A Tragedy in Posorja) details the repercussions of decades of neglect and indifference on the part of the police in rural areas, so much so that indigenous justice (“justice indigena”) was meted out, apparently mistakenly. And, in Mitzi Szereto’s, I Kill for God, there is again much detail about the investigative process, this time in Washington state, as well as informed discussion about mental health issues and the law, inconsistencies in such laws and the inadequacies of correctional institutions. So, …(I am a sociologist now), …and this book was appealing to me on all fronts (so to speak).

The authors tend to focus, not only on the crime, but on some ‘storyworthy’ aspect that may be of wider interest. In Snowtown (Southern Australia) the writer explores the stigma of what occurred there in 1999 and the impact on the town. I was initiated into new terms: dark tourism, black tourism, grief tourism, and thanatourism, as the debate unfolded about whether this very small town should exploit the murders for economic gain. Also set in Australia (Port Arthur, Tasmania), Nameless in van Dieman’s Land, sees the author grappling with how the community chose to efface any reference to the 2-day killing spree of 1996, even though it occurred in a much-visited, heritage site immemoralising Australia’s past as a penal colony. This crime in particular led to a ban on casual gun ownership in Australia. These “mega” crimes, committed in small towns, present a continuing dilemma to the people living there today.

Sometimes a crime happens that has so many elements of drama, suspense, and scandal that it morphs into a local legend. Such was the case of The Voodoo Preacher in Alabama, who murdered many members of his family and was shot at the funeral of one of his victims by another family member. The story reads like a Netflix mini-series and I feel like a viewer. It doesn’t displace my composure however, like Who Killed Gabrielle Schmidt, which chronicles the abduction and murder of a five year old girl, in 1983, in Fulda, Germany. There were no witnesses and remains unsolved. The author, a teenager at the time, traces the impact that this sad and horrifying incident had on her throughout her life and, how it continues to affect her now that she is the mother of a little girl. The Summer of the Fox, also takes up this theme that may resonate with readers, that even though unconnected to a particular crime, it has continued to endure somewhere in our individual lives.

I had come to this project with the idea that ‘sameness’ would be an inevitable feature of such a compilation, after all crime is crime, whether here or there. The authors however were quite adept at, what is called, ‘rich, thick description’ in qualitative research, taking the reader into the main events, the timelines, the suspects and their motivation, the arguments for and against, particularly if the crime was unsolved (Crime has Come to Penal). In this respect it was not that different from crime fiction when a detective such as Hercule Poirot assembles the likely suspects and the viability of their statements.

However, in true crime there is no ‘author’ in the shadows who knows all. Thus, in Bullets and Balaclavas, a murder was allegedly committed by a 15 year old boy in 1994, but there were so many twists and turns in the prosecution’s case, that he had become a soldier of some repute and a family man, by the time he faced charges in 2008. He was found guilty, but that verdict is still widely disputed and of 2020 his support campaign continues. In About A Boy we see the unwillingness and general disbelief of villagers to accept that an unassuming, 15 year old, murdered two little girls. Perhaps, this is the real message of the true crime genre – to nudge us into an understanding that ‘crime’ cannot be as easily explained as in bestsellers, that it can be irrational, unexpected, and will take us by surprise because, to a large extent, we are socialized into believing that things can be explained, if we try hard enough. And that is why, The Black Hand and Glass Eye of Earlimart, adds an important dimension to this anthology – the killer’s perspective.

“Armin Meiwes wanted to eat, and Bernd Brandes wanted to be eaten” (p. 211). I read In the House of the Cannibal, with morbid fascination. This is what crime fiction cannot do – it cannot boggle the imagination. Even if the subject is cannibalism, we know that it exists in the author’s head. But here, it really happened, and, with the consent of the ‘victim’! So, will I reach for another True Crime anthology when I’m next in the bookstore? Probably not, … maybe, but I know that I have overcome some kind of prejudice I had about the subject. But, I’m not going to read paranormal romance, ever!

Updated 4 years ago